Eastern Orthodox Church

Orthodox Catholic Church |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Type | Eastern Christian |

| Theology | Eastern Orthodox theology, Palamism |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Structure | Communion |

| Primus inter pares | Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I |

| Language | Koine Greek, Church Slavonic, Latin, and various vernaculars |

| Liturgy | Byzantine and Western |

| Founder | Jesus Christ, according to Holy Tradition |

| Origin | 1st century Holy Land, Roman Empire |

| Separations | Old Believers (17th century) True Orthodoxy (1920s) |

| Members | 260 million,[1] or approx. 262 million (3.7% of the world population)[2] |

| Other name(s) | Eastern Orthodox Church (very common), Orthodox Church, Orthodox Christian Church |

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

Mosaic of Christ Pantocrator, Hagia Sophia

|

| Overview |

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

The Eastern Orthodox Church, officially the Orthodox Catholic Church,[3][4][5][6] is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 260 million baptised members.[1][7][8][9][10] It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops in local synods.[9] Roughly half of Eastern Orthodox Christians live in Russia. The church has no central doctrinal or governmental authority analogous to the bishop of Rome, but the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople is recognised by all as primus inter pares (“first among equals”) of the bishops. As one of the oldest surviving religious institutions in the world, the Eastern Orthodox Church has played a prominent role in the history and culture of Eastern and Southeastern Europe, the Caucasus, and the Near East.[11]

Eastern Orthodox theology is based on the Nicene Creed. The church teaches that it is the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic church established by Jesus Christ in his Great Commission, and that its bishops are the successors of Christ’s apostles.[12] It maintains that it practices the original Christian faith, as passed down by holy tradition. Its patriarchates, reminiscent of the pentarchy, and autocephalous and autonomous churches reflect a variety of hierarchical organisation. It recognises seven major sacraments, of which the Eucharist is the principal one, celebrated liturgically in synaxis. The church teaches that through consecration invoked by a priest, the sacrificial bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ. The Virgin Mary is venerated in the Eastern Orthodox Church as the God-bearer, honoured in devotions.

The Eastern Orthodox Church shared communion with the Roman Catholic Church in the state church of Rome until the East–West Schism in 1054, disputing particularly the authority of the Pope. Before the Council of Ephesus in AD 431 the Church of the East also shared in this communion, as did the Oriental Orthodox Churches before the Council of Chalcedon in AD 451, all separating primarily over differences in Christology.

The majority of Eastern Orthodox Christians live mainly in Southeast and Eastern Europe, Cyprus, Georgia and other communities in the Caucasus region, and communities in Siberia reaching the Russian Far East. There are also smaller communities in the former Byzantine regions of Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean, and in the Middle East where it is decreasing due to forced migration because of increased religious persecution in recent years.[13][14] There are also many in other parts of the world, formed through diaspora, conversions, and missionary activity.

Name and characteristics

In keeping with the church’s teaching on universality and with the Nicene Creed, Orthodox authorities such as Saint Raphael of Brooklyn have insisted that the full name of the church has always included the term “Catholic“, as in “Holy Orthodox Catholic Apostolic Church”.[15][16][17] The official name of the Eastern Orthodox Church is the “Orthodox Catholic Church”.[3][4][5][6] It is the name by which the church refers to itself in its liturgical or canonical texts,[18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25] in official publications,[26][27] and in official contexts or administrative documents.[28][29] Orthodox teachers refer to the church as Catholic.[30][31] This name and longer variants containing “Catholic” are also recognised and referenced in other books and publications by secular or non-Orthodox writers.[32][33][34][35][36][37]

The common name of the church, “Eastern Orthodox Church”, is a shortened practicality that helps to avoid confusions in casual use. From ancient times through the first millennium, Greek was the most prevalent shared language in the demographic regions where the Byzantine Empire flourished, and Greek, being the language in which the New Testament was written, was the primary liturgical language of the church. For this reason, the eastern churches were sometimes identified as “Greek” (in contrast to the “Roman” or “Latin” church, which used a Latin translation of the Bible), even before the Great Schism of 1054. After 1054, “Greek Orthodox” or “Greek Catholic” marked a church as being in communion with Constantinople, much as “Catholic” did for communion with Rome. This identification with Greek, however, became increasingly confusing with time. Missionaries brought Orthodoxy to many regions without ethnic Greeks, where the Greek language was not spoken. In addition, struggles between Rome and Constantinople to control parts of Southeastern Europe resulted in the conversion of some churches to Rome, which then also used “Greek Catholic” to indicate their continued use of the Byzantine rites. Today, many of those same churches remain, while a very large number of Orthodox are not of Greek national origin, and do not use Greek as the language of worship.[38] “Eastern”, then, indicates the geographical element in the Church’s origin and development, while “Orthodox” indicates the faith, as well as communion with the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.[39] There are additional Christian churches in the east that are in communion with neither Rome nor Constantinople, who tend to be distinguished by the category named “Oriental Orthodox”. While the church continues officially to call itself “Catholic”, for reasons of universality, the common title of “Eastern Orthodox Church” avoids casual confusion with the Roman Catholic Church.

Orthodoxy

The first known use of the phrase “the catholic Church” (he katholike ekklesia) occurred in a letter written about 110 AD from one Greek church to another (Saint Ignatius of Antioch to the Smyrnaeans). The letter states: “Wheresoever the bishop shall appear, there let the people be, even as where Jesus may be, there is the universal [katholike] Church.”[40] Thus, almost from the very beginning, Christians referred to the Church as the “One, Holy, Catholic (from the Greek καθολική, or “according to the whole, universal”) and Apostolic Church”.[41] The Eastern Orthodox Church claims that it is today the continuation and preservation of that same early Church.

A number of other Christian churches also make a similar claim: the Roman Catholic Church, the Anglican Communion, the Assyrian Church and the Oriental Orthodox. In the Eastern Orthodox view, the Assyrians and Orientals left the Orthodox Church in the years following the Third Ecumenical Council of Ephesus (431) and the Fourth Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon (451), respectively, in their refusal to accept those councils’ Christological definitions. Similarly, the churches in Rome and Constantinople separated in an event known as the East–West Schism, traditionally dated to the year 1054, although it was more a gradual process than a sudden break. The Church of England separated from the Catholic Church, not directly from the Eastern Orthodox Church, for the first time in the 1530s (and, after a brief reunion in 1555, again finally in 1558). Thus, though it was united to Orthodoxy when established through the work of Saint Augustine of Canterbury in the early 7th century, its separation from Orthodoxy came about indirectly through the See of Rome.

To all these churches, the claim to catholicity (universality, oneness with the ancient Church) is important for multiple doctrinal reasons that have more bearing internally in each church than in their relation to the others, now separated in faith. The meaning of holding to a faith that is true is the primary reason why anyone’s statement of which church split off from which other has any significance at all; the issues go as deep as the schisms. The depth of this meaning in the Eastern Orthodox Church is registered first in its use of the word “Orthodox” itself, a union of Greek orthos (“straight”, “correct”, “true”, “right”) and doxa (“common belief”, from the ancient verb δοκέω-δοκῶ which is translated “to believe”, “to think”, “to consider”, “to imagine”, “to assume”).[42]

The dual meanings of doxa, with “glory” or “glorification” (of God by the Church and of the Church by God), especially in worship, yield the pair “correct belief” and “true worship”. Together, these express the core of a fundamental teaching about the inseparability of belief and worship and their role in drawing the church together with Christ.[43][44] The Bulgarian and all the Slavic churches use the title Pravoslavie (Cyrillic: Православие), meaning “correctness of glorification”, to denote what is in English Orthodoxy, while the Georgians use the title Martlmadidebeli. Several other churches in Europe, Asia, and Africa also came to use Orthodox in their titles, but are still distinct from the Eastern Orthodox Church as described in this article.

The term “Eastern Church” (the geographic east in the East–West Schism) has been used to distinguish it from western Christendom (the geographic West, which at first came to designate the Catholic communion, later also the various Protestant and Anglican branches). “Eastern” is used to indicate that the highest concentrations of the Eastern Orthodox Church presence remain in the eastern part of the Christian world, although it is growing worldwide. Orthodox Christians throughout the world use various ethnic or national jurisdictional titles, or more inclusively, the title “Eastern Orthodox”, “Orthodox Catholic”, or simply “Orthodox”.[39]

What unites Orthodox Christians is the catholic faith as carried through holy tradition. That faith is expressed most fundamentally in scripture and worship,[45] and the latter most essentially through baptism and in the Divine Liturgy.[46] Orthodox Christians proclaim the faith lives and breathes by God’s energies in communion with the church. Inter-communion is the litmus test by which all can see that two churches share the same faith; lack of inter-communion (excommunication, literally “out of communion”) is the sign of different faiths, even though some central theological points may be shared. The sharing of beliefs can be highly significant, but it is not the full measure of the faith according to the Orthodox.

The lines of even this test can blur, however, when differences that arise are not due to doctrine, but to recognition of jurisdiction. As the Eastern Orthodox Church has spread into the west and over the world, the church as a whole has yet to sort out all the inter-jurisdictional issues that have arisen in the expansion, leaving some areas of doubt about what is proper church governance.[47] And as in the ancient church persecutions, the aftermath of persecutions of Christians in communist nations has left behind both some governance and some faith issues that have yet to be completely resolved.[48]

All members of the Eastern Orthodox Church profess the same faith, regardless of race or nationality, jurisdiction or local custom, or century of birth. Holy tradition encompasses the understandings and means by which that unity of faith is transmitted across boundaries of time, geography, and culture. It is a continuity that exists only inasmuch as it lives within Christians themselves.[49] It is not static, nor an observation of rules, but rather a sharing of observations that spring both from within and also in keeping with others, even others who lived lives long past. The church proclaims the Holy Spirit maintains the unity and consistency of holy tradition to preserve the integrity of the faith within the church, as given in the scriptural promises.[50]

The shared beliefs of Orthodoxy, and its theology, exist within Holy Tradition and cannot be separated from it, for their meaning is not expressed in mere words alone.[51] Doctrine cannot be understood unless it is prayed.[52] Doctrine must also be lived in order to be prayed, for without action, the prayer is idle and empty, a mere vanity, and therefore the theology of demons.[53] According to these teachings of the ancient Church, no superficial belief can ever be orthodox. Similarly, reconciliation and unity are not superficial, but are prayed and lived out.

Catholicity

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

The Eastern Orthodox Church considers itself to be both orthodox and catholic. The doctrine of the Catholicity of the Church, as derived from the Nicene Creed, is essential to Eastern Orthodox ecclesiology. The term Catholicity of the Church (Greek Καθολικότης τῆς Ἐκκλησίας) is used in its original sense, as a designation for the Universality of the Church, centered around Christ. Therefore, the Eastern Orthodox notion of catholicity is not centered around any singular see, unlike Catholicism, that has one earthly center.

Due to the influence of the Catholic Church in the west, where the English language itself developed, the words “catholic” and “catholicity” are sometimes used to refer to that church specifically. However, the more prominent dictionary sense given for general use is still the one shared by other languages, implying breadth and universality, reflecting comprehensive scope.[54] In a Christian context, the Christian Church, as identified with the original Church founded by Christ and his apostles, is said to be catholic (or universal) in regard to its union with Christ in faith. Just as Christ is indivisible, so are union with him and faith in him, whereby the Church is “universal”, unseparated, and comprehensive, including all who share that faith. Orthodox bishop Kallistos Ware has called that “simple Christianity”.[55] That is the sense of early and patristic usage wherein the church usually refers to itself as the “Catholic Church”,[56][57] whose faith is the “Orthodox faith”. It is also the sense within the phrase “One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church”, found in the Nicene Creed, and referred to in Orthodox worship, e.g. in the litany of the catechumens in the Divine Liturgy.

With the mutual excommunications of the East–West Schism in 1054, the churches in Rome and Constantinople each viewed the other as having departed from the true Church, leaving a smaller but still-catholic church in place. Each retained the “Catholic” part of its title, the “Roman Catholic Church” (or Catholic Church) on the one hand, and the “Orthodox Catholic Church” on the other, each of which was defined in terms of inter-communion with either Rome or Constantinople. While the Eastern Orthodox Church recognises what it shares in common with other churches, including the Catholic Church, it sees catholicity in terms of complete union in communion and faith, with the Church throughout all time, and the sharing remains incomplete when not shared fully.

Organisation and leadership

The religious authority for Eastern Orthodoxy is not a patriarch or the Bishop of Rome as in Catholicism, nor the Bible as in Protestantism, but the scriptures as interpreted by the seven ecumenical councils of the Imperial Roman Church. The Eastern Orthodox Church is a fellowship of “autocephalous” (Greek for self-headed) churches, with the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople being the only autocephalous head who holds the title primus inter pares, meaning “first among equals” in Latin. The Patriarch of Constantinople has the honor of primacy, but his title is only first among equals and has no real authority over churches other than the Constantinopolitan,[58][59][60] though at times the office of the Ecumenical Patriarch has been accused of Constantinopolitan or Eastern papism.[61][62] The Eastern Orthodox Church considers Jesus Christ to be the head of the church and the church to be his body. It is believed that authority and the grace of God is directly passed down to Orthodox bishops and clergy through the laying on of hands—a practice started by the apostles, and that this unbroken historical and physical link is an essential element of the true Church (Acts 8:17, 1 Tim 4:14, Heb 6:2). The Orthodox Church asserts that apostolic succession requires apostolic faith, and bishops without apostolic faith, who are in heresy, forfeit their claim to apostolic succession.[63]

The Eastern Orthodox communion is organised into several regional churches, which are either autocephalous (“self-headed”) or lower ranking autonomous (the Greek term for “self-lawed”) church bodies unified in theology and worship. These include the fourteen autocephalous churches of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem, Georgia, Cyprus, Bulgaria, Serbia, Russia, Greece, Poland, Romania, Albania, and the Czech Republic and Slovakia, which were officially invited to the Pan-Orthodox Council of 2016,[64] the Orthodox Church in America formed in 1970, the autocephalous Orthodox Church of Ukraine created in 2019, as well as a number of autonomous churches.[59] Each church has a ruling bishop and a holy synod to administer its jurisdiction and to lead the Orthodox Church in the preservation and teaching of the apostolic and patristic traditions and church practices.

Each bishop has a territory (see) over which he governs.[60] His main duty is to make sure the traditions and practices of the Orthodox Church are preserved. Bishops are equal in authority and cannot interfere in the jurisdiction of another bishop. Administratively, these bishops and their territories are organised into various autocephalous groups or synods of bishops who gather together at least twice a year to discuss the state of affairs within their respective sees. While bishops and their autocephalous synods have the ability to administer guidance in individual cases, their actions do not usually set precedents that affect the entire Eastern Orthodox Church. Bishops are almost always chosen from the monastic ranks and must remain unmarried.

Church councils

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

There have been a number of times when alternative theological ideas arose to challenge the Orthodox faith. At such times the Orthodox communion deemed it necessary to convene a general or “great” council of all available bishops throughout the world. The Orthodox Church holds that seven ecumenical councils, held between the 4th and the 8th centuries, are authoritative.

The ecumenical councils followed a democratic form, with each bishop having one vote. Though present and allowed to speak before the council, members of the Imperial Roman/Byzantine court, abbots, priests, deacons, monks and laymen were not allowed to vote. The primary goal of these great synods was to verify and confirm the fundamental beliefs of the Great Christian Church as truth, and to remove as heresy any false teachings that would threaten the Church. The Pope of Rome at that time held the position of “Primus inter pares” (“first among equals”) and, while he was not present at any of the councils, he continued to hold this title until the East–West Schism of 1054.

Other councils have helped to define the Eastern Orthodox position, specifically the Quinisext Council, the Synods of Constantinople, 879–880, 1341, 1347, 1351, 1583, 1819, and 1872, the Synod of Jassy (Iași), 1642, and the Pan-Orthodox Synod of Jerusalem, 1672; the Pan-Orthodox Council, held in Greece in 2016, was the only such Eastern Orthodox council in modern times.

According to Orthodox teaching the position of “first among equals” gives no additional power or authority to the bishop that holds it, but rather that this person sits as organizational head of a council of equals (like a president). His words and opinions carry no more insight or wisdom than any other bishop. It is believed that the Holy Spirit guides the Eastern Orthodox Church through the decisions of the entire council, not one individual. Additionally it is understood that even the council’s decisions must be accepted by the entire Orthodox Church in order for them to be valid.

One of the decisions made by the First Council of Constantinople (the second ecumenical council, meeting in 381) and supported by later such councils was that the Patriarch of Constantinople should be given equal honor to the Pope of Rome since Constantinople was considered to be the “New Rome“. According to the third canon of the second ecumenical council: “Because it is new Rome, the bishop of Constantinople is to enjoy the privileges of honor after the bishop of Rome.” This means that both enjoy the same privileges because they are both bishops of the imperial capitals, but the bishop of Rome will precede the bishop of Constantinople since Old Rome precedes New Rome.

The 28th canon of the fourth ecumenical council clarified this point by stating: “For the Fathers rightly granted privileges to the throne of Old Rome because it was the royal city. And the One Hundred and Fifty most religious Bishops (i.e. the second ecumenical council in 381) actuated by the same consideration, gave equal privileges to the most holy throne of New Rome, justly judging that the city which is honoured with the Sovereignty and the Senate, and enjoys equal privileges with the old imperial Rome, should in ecclesiastical matters also be magnified as she is.”

Because of the schism the Eastern Orthodox no longer recognise the primacy of the Pope of Rome. The Patriarch of Constantinople therefore, like the Pope before him, now enjoys the title of “first among equals”.

Adherents

Politics, wars, persecutions, oppressions, and related potential threats[65] can make precise counts of Orthodox membership difficult to obtain at best in some regions. Historically, forced migrations have also altered demographics in relatively short periods of time. The most reliable estimates currently available number Orthodox adherents at around 200 million worldwide,[58] making Eastern Orthodoxy the second largest Christian communion in the world after the Catholic Church.[66] The numerous Protestant groups in the world, if taken all together, outnumber the Eastern Orthodox,[67] but they differ theologically and do not form a single communion.[66] According to the 2015 Yearbook of International Religious Demography, the Eastern Orthodox population in 2010 decreased to 4% of the global population from 7.1% of the global population in 1910. According to the same source, in terms of the total Christian population, the relative percentages were 12.2% and 20.4% respectively.[68] According to the Pew Research Center, the Eastern Orthodox share of the world’s total Christian population was 12% in 2011.[inconsistent][discuss][69](p21)

Most members today are concentrated in Eastern Europe and Asian Russia, in addition to significant minorities in Central Asia and the Levant, although Eastern Orthodoxy has spread into a global religion towards Western Europe and the New World, with churches in most countries and major cities. The adherents constitute the largest single religious faith in the world’s largest country—Russia,[70][a] where roughly half of Eastern Orthodox Christians live. They are the majority religion in Ukraine,[72][73] Romania,[72] Belarus,[74] Greece,[b][72] Serbia,[72] Bulgaria,[72] Moldova,[72] Georgia,[72] North Macedonia,[72] Cyprus,[72] and Montenegro;[72] they also dominate in the disputed territories of Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Transnistria. Significant minorities of Eastern Orthodox are present in Bosnia and Herzegovina (absolute majority in Republika Srpska),[72] Latvia,[75] Estonia,[76] Kazakhstan,[77] Kyrgyzstan,[78] Lebanon,[79] Albania, Syria,[72] and many other countries.

The percentage of Christians in Turkey fell from 19 percent in 1914 to 2.5 percent in 1927,[80] predominantly due to persecution, including the Armenian Holocaust, the Greek genocide and subsequent population exchange between Greece and Turkey,[81] population exchanges between Bulgaria and Turkey, and associated emigration of Christians to foreign countries (mostly in Europe and the Americas).[82] Today there are more than 160,000 people (about 0.2%) of different Christian denominations.[72]

Through mostly labor migration from Eastern Europe and some conversion, Orthodox Christianity is the fastest growing religious grouping in certain Western countries, for example in the Republic of Ireland,[83][84][85] but Orthodoxy is not “a central marker of minority identity” for the migrants.[83] While in the United States, the number of Orthodox parishes is growing.[86][c][d]

Theology

Trinity

Orthodox Christians believe in the Trinity, three distinct, divine persons (hypostases), without overlap or modality among them, who each have one divine essence (ousia Greek οὐσία)—uncreated, immaterial and eternal.[90] These three persons are typically distinguished by their relation to each other. The Father is eternal and not begotten and does not proceed from any, the Son is eternal and begotten of the Father, and the Holy Spirit is eternal and proceeds from the Father. Orthodox doctrine regarding the Trinity is summarised in the Nicene Creed.[91]

In discussing God’s relationship to his creation, Orthodox theology distinguishes between God’s eternal essence, which is totally transcendent, and his uncreated energies, which is how he reaches humanity. The God who is transcendent and the God who touches mankind are one and the same. That is, these energies are not something that proceed from God or that God produces, but rather they are God himself: distinct, yet inseparable from God’s inner being.[92]

In understanding the Trinity as “one God in three persons”, “three persons” is not to be emphasised more than “one God”, and vice versa. While the three persons are distinct, they are united in one divine essence, and their oneness is expressed in community and action so completely that they cannot be considered separately. For example, their salvation of mankind is an activity engaged in common: “Christ became man by the good will of the Father and by the cooperation of the Holy Spirit. Christ sends the Holy Spirit who proceeds from the Father, and the Holy Spirit forms Christ in our hearts, and thus God the Father is glorified.” Their “communion of essence” is “indivisible”. Trinitarian terminology—essence, hypostasis, etc.—are used “philosophically”, “to answer the ideas of the heretics”, and “to place the terms where they separate error and truth.”[93] The words do what they can do, but the nature of the Trinity in its fullness is believed to remain beyond man’s comprehension and expression, a holy mystery that can only be experienced.

Sin, salvation, and the incarnation

According to the Eastern Orthodox faith, at some point in the beginnings of human existence, humanity was faced with a choice: to learn the difference between good and evil through observation or through participation. The biblical story of Adam and Eve relates this choice by mankind to participate in evil, accomplished through disobedience to God’s command. Both the intent and the action were separate from God’s will; it is that separation that defines and marks any operation as sin. The separation from God caused the loss of (fall from) his grace, a severing of mankind from his creator and the source of his life. The end result was the diminishment of human nature and its subjection to death and corruption, an event commonly referred to as the “fall of man”.

When Orthodox Christians refer to fallen nature they are not saying that human nature has become evil in itself. Human nature is still formed in the image of God; humans are still God’s creation, and God has never created anything evil, but fallen nature remains open to evil intents and actions. It is sometimes said among Orthodox that humans are “inclined to sin”; that is, people find some sinful things attractive. It is the nature of temptation to make sinful things seem the more attractive, and it is the fallen nature of humans that seeks or succumbs to the attraction. Orthodox Christians reject the Augustinian position that the descendants of Adam and Eve are actually guilty of the original sin of their ancestors.[94] But just as any species begets its own kind, so fallen humans beget fallen humans, and from the beginning of humanity’s existence people lie open to sinning by their own choice.

Since the fall of man, then, it has been mankind’s dilemma that no human can restore his nature to union with God’s grace; it was necessary for God to effect another change in human nature. Orthodox Christians believe that Christ Jesus was both God and Man absolutely and completely, having two natures indivisibly: eternally begotten of the Father in his divinity, he was born in his humanity of a woman, Mary, by her consent, through descent of the Holy Spirit. He lived on earth, in time and history, as a man. As a man he also died, and went to the place of the dead, which is Hades. But being God, neither death nor Hades could contain him, and he rose to life again, in his humanity, by the power of the Holy Spirit, thus destroying the power of Hades and of death itself.[95] Through God’s participation in humanity, Christ’s human nature, perfected and unified with his divine nature, ascended into heaven, there to reign in communion with the Father and Holy Spirit.

By these acts of salvation, Christ provided fallen mankind with the path to escape its fallen nature. The Eastern Orthodox Church teaches that through baptism into Christ’s death, and a person’s death unto sin in repentance, with God’s help mankind can also rise with Christ into heaven, healed of the breach of man’s fallen nature and restored to God’s grace. To Orthodox Christians, this process is what is meant by “salvation,” which consists of the Christian life. The ultimate goal is theosis an even closer union with God and closer likeness to God than existed in the Garden of Eden. This process is called Deification or “God became man that man might become ‘god'”. However, it must be emphasised that Orthodox Christians do not believe that man becomes God in his essence, or a god in his own nature. More accurately, Christ’s salvific work enables man in his human nature to become “partakers of the Divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4); that is to say, man is united to God in Christ.

Through Christ’s destruction of Hades’ power to hold humanity hostage, he made the path to salvation effective for all the righteous who had died from the beginning of time—saving many, including Adam and Eve, who are remembered in the Church as saints.[96]

The Eastern Orthodox reject the idea that Christ died to give God “satisfaction” as taught by Anselm, or as a punitive substitute as taught by the Reformers. Sin (separation from God, who is the source of all life) is its own punishment, capable of imprisoning the soul in an existence without life, without anything good, and without hope: hell by any measure. Life on earth is God’s gift, to give humankind opportunity to make their choice real: separation or union.[citation needed]

Resurrection of Christ

The Eastern Orthodox Church understands the death and resurrection of Jesus to be real historical events, as described in the gospels of the New Testament. Jesus Christ, the Son of God, is believed to, according to Orthodox teaching, in his humanity be (that is, in history) crucified, and died, descending into Hades (Sheol), the place of the dead, as all humans do. But he, alone among humans, has two natures, one human, one divine, which are indivisible and inseparable from each other through the mystery of the incarnation. Hades could not restrain the infinite God. Christ in his divine nature captured the keys of Hades and broke the bonds which had imprisoned the human souls who had been held there through their separation from God.

Neither could death contain the Son of God, the Fountain of Life, who arose from death even in his human nature. Not only this, but he opened the gates of Hades to all the righteous dead of past ages, rescuing them from their fallen human nature and restoring them to a nature of grace with God, bringing them back to life, this time in God’s heavenly kingdom. And this path he opened to all who choose to follow him in time yet to come, thus saving the human race. Thus the Eastern Orthodox proclaim each year at the time of Pascha (Easter), that Christ “trampled down death by death, and on those in the tombs bestowed life.”

The celebration of the Resurrection of Christ at Pascha is the central event in the liturgical year of the Eastern Orthodox Church. According to Orthodox tradition, each human being may partake of this immortality, which would have been impossible without the Resurrection; it is the main promise held out by God in the New Testament. Every holy day of the Eastern Orthodox liturgical year relates to the Resurrection directly or indirectly. Every Sunday is especially dedicated to celebrating the Resurrection and the triune God, representing a mini-Pascha. In the liturgical commemorations of the Passion of Christ during Holy Week there are frequent allusions to the ultimate victory at its completion.

Christian life

Church teaching is that Orthodox Christians, through baptism, enter a new life of salvation through repentance whose purpose is to share in the life of God through the work of the Holy Spirit. The Eastern Orthodox Christian life is a spiritual pilgrimage in which each person, through the imitation of Christ and hesychasm,[97] cultivates the practice of unceasing prayer. Each life occurs within the life of the church as a member of the body of Christ.[98] It is then through the fire of God’s love in the action of the Holy Spirit that each member becomes more holy, more wholly unified with Christ, starting in this life and continuing in the next.[99][100] The church teaches that everyone, being born in God’s image, is called to theosis, fulfillment of the image in likeness to God. God the creator, having divinity by nature, offers each person participation in divinity by cooperatively accepting His gift of grace.[101]

The Eastern Orthodox Church, in understanding itself to be the Body of Christ, and similarly in understanding the Christian life to lead to the unification in Christ of all members of his body, views the church as embracing all Christ’s members, those now living on earth, and also all those through the ages who have passed on to the heavenly life. The church includes the Christian saints from all times, and also judges, prophets and righteous Jews of the first covenant, Adam and Eve, even the angels and heavenly hosts.[102] In Orthodox services, the earthly members together with the heavenly members worship God as one community in Christ, in a union that transcends time and space and joins heaven to earth. This unity of the Church is sometimes called the communion of the saints.[103]

Virgin Mary and other saints

The Eastern Orthodox Church believes death and the separation of body and soul to be unnatural—a result of the Fall of Man. They also hold that the congregation of the church comprises both the living and the dead. All persons currently in heaven are considered to be saints, whether their names are known or not. There are, however, those saints of distinction whom God has revealed as particularly good examples. When a saint is revealed and ultimately recognised by a large portion of the church a service of official recognition (canonization) is celebrated.

This does not “make” the person a saint; it merely recognises the fact and announces it to the rest of the church. A day is prescribed for the saint’s celebration, hymns composed and icons created. Numerous saints are celebrated on each day of the year. They are venerated (shown great respect and love) but not worshipped, for worship is due God alone (this view is also held by the Oriental Orthodox and Catholic Churches). In showing the saints this love and requesting their prayers, the Eastern Orthodox manifest their belief that the saints thus assist in the process of salvation for others.

Pre-eminent among the saints is the Virgin Mary (commonly referred to as Theotokos or Bogoroditsa) (“Mother of God“). In Orthodox theology, the Mother of God is the fulfillment of the Old Testament archetypes revealed in the Ark of the Covenant (because she carried the New Covenant in the person of Christ) and the burning bush that appeared before Moses (symbolizing the Mother of God’s carrying of God without being consumed).[104] Accordingly, the Eastern Orthodox consider Mary to be the Ark of the New Covenant and give her the respect and reverence as such. The Theotokos, in Orthodox teaching, was chosen by God and she freely co-operated in that choice to be the Mother of Jesus Christ, the God-man.

The Eastern Orthodox believe that Christ, from the moment of his conception, was both fully God and fully human. Mary is thus called the Theotokos or Bogoroditsa as an affirmation of the divinity of the one to whom she gave birth. It is also believed that her virginity was not compromised in conceiving God-incarnate, that she was not harmed and that she remained forever a virgin. Scriptural references to “brothers” of Christ are interpreted as kin, given that the word “brother” was used in multiple ways, as was the term “father”. Due to her unique place in salvation history, Mary is honoured above all other saints and especially venerated for the great work that God accomplished through her.[105]

The Eastern Orthodox Church regards the bodies of all saints as holy, made such by participation in the holy mysteries, especially the communion of Christ’s holy body and blood, and by the indwelling of the Holy Spirit within the church. Indeed, that persons and physical things can be made holy is a cornerstone of the doctrine of the Incarnation, made manifest also directly by God in Old Testament times through his dwelling in the Ark of the Covenant. Thus, physical items connected with saints are also regarded as holy, through their participation in the earthly works of those saints. According to church teaching and tradition, God himself bears witness to this holiness of saints’ relics through the many miracles connected with them that have been reported throughout history since Biblical times, often including healing from disease and injury.[106]

Eschatology

Orthodox Christians believe that when a person dies the soul is temporarily separated from the body. Though it may linger for a short period on Earth, it is ultimately escorted either to paradise (Abraham’s bosom) or the darkness of Hades, following the Temporary Judgment. Orthodox do not accept the doctrine of Purgatory, which is held by Catholicism. The soul’s experience of either of these states is only a “foretaste”—being experienced only by the soul—until the Final Judgment, when the soul and body will be reunited.[107][108]

The Eastern Orthodox believe that the state of the soul in Hades can be affected by the love and prayers of the righteous up until the Last Judgment.[109] For this reason the Church offers a special prayer for the dead on the third day, ninth day, fortieth day, and the one-year anniversary after the death of an Orthodox Christian. There are also several days throughout the year that are set aside for general commemoration of the departed, sometimes including nonbelievers. These days usually fall on a Saturday, since it was on a Saturday that Christ lay in the Tomb.[108]

While the Eastern Orthodox consider the text of the Apocalypse (Book of Revelation) to be a part of Scripture, it is also regarded to be a holy mystery. Speculation on the contents of Revelation are minimal and it is never read as part of the regular order of services.[citation needed] Those theologians who have delved into its pages tend to be amillennialist in their eschatology, believing that the “thousand years” spoken of in biblical prophecy refers to the present time: from the Crucifixion of Christ until the Second Coming.

While it is not usually taught in church it is often used as a reminder of God’s promise to those who love him, and of the benefits of avoiding sinful passions. Iconographic depictions of the Final Judgment are often portrayed on the back (western) wall of the church building to remind the departing faithful to be vigilant in their struggle against sin. Likewise it is often painted on the walls of the Trapeza (refectory) in a monastery where monks may be inspired to sobriety and detachment from worldly things while they eat.

The Eastern Orthodox believe that Hell, though often described in metaphor as punishment inflicted by God, is in reality the soul’s rejection of God’s infinite love which is offered freely and abundantly to everyone.

The Eastern Orthodox believe that after the Final Judgment:

- All souls will be reunited with their resurrected bodies.

- All souls will fully experience their spiritual state.

- Having been perfected, the saints will forever progress towards a deeper and fuller love of God, which equates with eternal happiness.[108]

Bible

The official Bible of the Eastern Orthodox Church contains the Septuagint text of the Old Testament, with the Book of Daniel given in the translation by Theodotion. The Patriarchal Text is used for the New Testament.[110][111][112] Orthodox Christians hold that the Bible is a verbal icon of Christ, as proclaimed by the 7th ecumenical council.[113] They refer to the Bible as Holy Scripture, meaning writings containing the foundational truths of the Christian faith as revealed by Christ and the Holy Spirit to its divinely inspired human authors. Holy Scripture forms the primary and authoritative written witness of Holy Tradition and is essential as the basis for all Orthodox teaching and belief.[114] The Bible provides the only texts held to be suitable for reading in Orthodox worship services. Through the many scriptural quotations embedded in the worship service texts themselves, it is often said that the Eastern Orthodox pray the Bible as well as read it.

St. Jerome completed the well-known Vulgate Latin translation only in the early 5th century, around the time the accepted lists of scripture were resolved in the west. The east took up to a century longer to resolve the lists in use there, and ended by accepting a few additional writings from the Septuagint that did not appear in the lists of the west. The differences were small and were not considered to compromise the unity of the faith shared between east and west. They did not play a role in the eventual schism in the 11th century that separated the See of Rome and the West from the See of Constantinople and the other apostolic Orthodox churches, and remained as defined essentially without controversy in the East or West for at least one thousand years. It was only in the 16th century that Reformation Protestants challenged the lists, proclaiming a canon that rejected those Old Testament books that did not appear in the 3rd-century Hebrew Bible. In response, the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches reaffirmed their accepted scriptural lists in more formal canons of their own.

Once established as Holy Scripture, there has never been any question that the Eastern Orthodox Church holds the full list of books to be venerable and beneficial for reading and study,[115] even though it informally holds some books in higher esteem than others, the four gospels highest of all. Of the subgroups significant enough to be named, the “Anagignoskomena” (ἀναγιγνωσκόμενα, “things that are read”) comprises ten of the Old Testament books rejected in the Protestant canon,[116] but deemed by the Eastern Orthodox worthy to be read in worship services, even though they carry a lesser esteem than the 39 books of the Hebrew canon.[117] The lowest tier contains the remaining books not accepted by either Protestants or Catholics, among them, Psalm 151. Though it is a psalm, and is in the book of psalms, it is not classified as being within the Psalter (the first 150 psalms),[118] and hence does not participate in the various liturgical and prayer uses of the Psalter.

In a very strict sense, it is not entirely orthodox to call the Holy Scriptures the “Word of God”. That is a title the Eastern Orthodox Church reserves for Christ, as supported in the scriptures themselves, most explicitly in the first chapter of the gospel of John. God’s Word is not hollow, like human words. “God said, ‘let there be light’; and there was light.”[119] This is the Word which spoke the universe into being, and resonates in creation without diminution throughout all history, a Word of divine power.

As much as the Eastern Orthodox Church reveres and depends on the scriptures, they cannot compare to the Word of God’s manifest action. But the Eastern Orthodox do believe that the Holy Scriptures testify to God’s manifest actions in history, and that through its divine inspiration God’s Word is manifested both in the scriptures themselves and in the cooperative human participation that composed them. It is in that sense that the Eastern Orthodox refer to the scriptures as “God’s Word”.

The Eastern Orthodox Church does not subscribe to the Protestant doctrine of sola scriptura. The church has defined what Scripture is; it also interprets what its meaning is.[120] Christ promised: “When He, the Spirit of truth, has come, He will guide you into all truth”.[121] The Holy Spirit, then, is the infallible guide for the church to the interpretation of Scripture. The church depends upon those saints who, by lives lived in imitation of Christ, achieving theosis, can serve as reliable witnesses to the Holy Spirit’s guidance. Individual interpretation occurs within the church and is informed by the church. It is rational and reasoned, but is not arrived at only by means of deductive reasoning.

Scriptures are understood to contain historical fact, poetry, idiom, metaphor, simile, moral fable, parable, prophecy and wisdom literature, and each bears its own consideration in its interpretation. While divinely inspired, the text stills consists of words in human languages, arranged in humanly recognizable forms. The Eastern Orthodox Church does not oppose honest critical and historical study of the Bible.[122] In biblical interpretation, it does not use speculations, suggestive theories, or incomplete indications, not going beyond what is fully known.

Holy Tradition and the patristic consensus

“That faith which has been believed everywhere, always, and by all”, the faith taught by Jesus to the apostles, given life by the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, and passed down to future generations without additions and without subtractions, is known as holy tradition.[123][124] Holy tradition does not change in the Eastern Orthodox Church because it encompasses those things that do not change: the nature of the one God in Trinity, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, the history of God’s interactions with his peoples, the Law as given to the Israelites, all Christ’s teaching as given to the disciples and Jews and recorded in scripture, including the parables, the prophecies, the miracles, and his own example to humanity in his extreme humility. It encompasses also the worship of the church, which grew out of the worship of the synagogue and temple and was extended by Christ at the last supper, and the relationship between God and his people which that worship expresses, which is also evidenced between Christ and his disciples. It includes the authority that Christ bestowed on his disciples when he made them apostles,[125] for the preserving and teaching of the faith, and for governing the organization and conduct of the church (in its administration by bishops).

Holy tradition is firm, even unyielding, but not rigid or legalistic; instead, it lives and breathes within the church.[126] For example, the New Testament was entirely written by the early church (mostly the apostles). The whole Bible was accepted as scripture by means of holy tradition practiced within the early church. The writing and acceptance took five centuries, by which time the Holy Scriptures themselves had become in their entirety a part of holy tradition.[127] But holy tradition did not change, because “that faith which has been believed everywhere, always, and by all” remained consistent, without additions, and without subtractions. The historical development of the Divine Liturgy and other worship services and devotional practices of the church provide a similar example of extension and growth “without change”.[128]

The continuity and stability of Orthodox worship throughout the centuries is one means by which holy tradition expresses the unity of the whole church throughout time. Not only can the Eastern Orthodox of today visit a church in a place that speaks a language unknown to the visitors yet have the service remain familiar and understandable to them, but the same would hold true were any able to visit past eras. The church strives to preserve holy tradition “unchanging” that it may express the one unchanging faith for all time to come as well.

Besides these, holy tradition includes the doctrinal definitions and statements of faith of the seven ecumenical councils, including the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, and some later local councils, patristic writings, canon law, and icons.[122] Not all portions of holy tradition are held to be equally strong. Some, the Holy Scriptures foremost, certain aspects of worship, especially in the Divine Liturgy, the doctrines of the ecumenical councils, the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, possess a verified authority that endures forever, irrevocably.[122] However, with local councils and patristic writings, the church applies a selective judgement. Some councils and writers have occasionally fallen into error, and some contradict each other.[122]

In other cases, opinions differ, no consensus is forthcoming, and all are free to choose. With agreement among the Church Fathers, though, the authority of interpretation grows, and full patristic consensus is very strong. With canon law (which tends to be highly rigorous and very strict, especially with clergy) an unalterable validity also does not apply, since canons deal with living on earth, where conditions are always changing and each case is subject to almost infinite variation from the next.[122] Even when and where they were once used with full strictness, their application was not absolute, and was carried out for individuals under the pastoral care of their bishop, who had the authority to decide when individual discipline had been satisfied. This too is a part of the holy tradition.

By tradition, the Eastern Orthodox Church, when faced with issues that are larger than a single bishop can resolve, holds a local council. The bishops and such others as may attend convene (as St. Paul called the Corinthians to do) to seek the mind of the church.[129] A council’s declarations or edicts then reflect its consensus (if one can be found). An ecumencial council is only called for issues of such import or difficulty or pervasiveness that smaller councils are insufficient to address them. Ecumenical councils’ declarations and canons carry binding weight by virtue of their representation across the whole church, by which the mind of the church can be readily seen. However, not all issues are so difficult as to require an ecumenical council to resolve. Some doctrines or decisions, not defined in a formal statement or proclaimed officially, nevertheless are held by the church unshakably and unanimously without internal disturbance, and these, also reflecting the mind of the church, are just as firmly irrevocable as a formal declaration of an ecumenical council. Lack of formality does not imply lack of authority within holy tradition.[122] An example of such unanimity can be found in the acceptance in the 5th century of the lists of books that comprise Holy Scripture, a true canon without official stamp.

Territorial expansion and doctrinal integrity

During the course of the early church, there were numerous followers who attached themselves to the Christ and his mission here on Earth, as well as followers who retained the distinct duty of being commissioned with preserving the quality of life and lessons revealed through the experience of Jesus living, dying, resurrecting and ascending among them. As a matter of practical distinction and logistics, people of varying gifts were accorded stations within the community structure— ranging from the host of agape meals (shared with brotherly and fatherly love), to prophecy and the reading of Scripture, to preaching and interpretations and giving aid to the sick and the poor. Sometime after Pentecost the Church grew to a point where it was no longer possible for the Apostles to minister alone. Overseers (bishops)[130] and assistants (deacons and deaconesses)[131] were appointed to further the mission of the Church.

The church recognised the gathering of these early church communities as being greatest in areas of the known world that were famous for their significance on the world stage—either as hotbeds of intellectual discourse, high volumes of trade, or proximity to the original sacred sites. These locations were targeted by the early apostles, who recognised the need for humanitarian efforts in these large urban centers and sought to bring as many people as possible into the church—such a life was seen as a form of deliverance from the decadent lifestyles promoted throughout the eastern and western Roman empires.

As the church increased in size through the centuries, the logistic dynamics of operating such large entities shifted: patriarchs, metropolitans, archimandrites, abbots and abbesses, all rose up to cover certain points of administration.[132]

As a result of heightened exposure and popularity of the philosophical schools (haereseis) of Greco-Roman society and education, synods and councils were forced to engage such schools that sought to co-opt the language and pretext of the Christian faith in order to gain power and popularity for their own political and cultural expansion. As a result, ecumenical councils were held to attempt to rebuild solidarity by using the strength of distant orthodox witnesses to dampen the intense local effects of particular philosophical schools within a given area.

While originally intended to serve as an internal check and balance for the defense of the doctrine developed and spread by the apostles to the various sees against faulty local doctrine, at times the church found its own bishops and emperors falling prey to local conventions. At these crucial moments in the history of the church, it found itself able to rebuild on the basis of the faith as it was kept and maintained by monastic communities, who subsisted without reliance on the community of the state or popular culture and were generally unaffected by the materialism and rhetoric that often dominated and threatened the integrity and stability of the urban churches.

In this sense, the aim of the councils was not to expand or fuel a popular need for a clearer or relevant picture of the original apostolic teaching. Rather, the theologians spoke to address the issues of external schools of thought who wished to distort the simplicity and neutrality of the apostolic teaching for personal or political gain. The consistency of the Eastern Orthodox faith is entirely dependent on the Holy Tradition of the accepted corpus of belief–the decisions ratified by the fathers of the seven ecumenical councils, and this is only done at the beginning of a consecutive council so that the effects of the decisions of the prior council can be audited and verified as being both conceptually sound and pragmatically feasible and beneficial for the church as a whole.

Worship

Church calendar

One part of the autocephalous Orthodox churches follows the Julian calendar, while the other part follows the Revised Julian calendar. The autonomous Church of Finland of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, as well as parts of the Church of the Czech Lands and Slovakia, use the Gregorian calendar.[citation needed] Many church traditions, including the schedules of services, feasts, and fasts, are structured by the church’s calendar, which provides a strictly observed intermingled set of cycles of varying lengths. The fixed annual cycle begins on 1 September and establishes the times for all annual observances that are fixed by date, such as Christmas. The annual Paschal cycle is established relative to the varying date of Pascha each year and affects the times for such observances as Pascha itself, Great Lent, Holy Week, and the feasts of Ascension and Pentecost.

Lesser cycles also run in tandem with the annual ones. A weekly cycle of days prescribes a specific focus for each day in addition to others that may be observed.[133]

Each day of the Weekly Cycle is dedicated to certain special memorials. Sunday is dedicated to Christ’s Resurrection; Monday honors the holy bodiless powers (angels, archangels, etc.); Tuesday is dedicated to the prophets and especially the greatest of the prophets, St. John the Forerunner and Baptist of the Lord; Wednesday is consecrated to the Cross and recalls Judas’ betrayal; Thursday honors the holy apostles and hierarchs, especially St. Nicholas, Bishop of Myra in Lycia; Friday is also consecrated to the Cross and recalls the day of the Crucifixion; Saturday is dedicated to All Saints, especially the Mother of God, and to the memory of all those who have departed this life in the hope of resurrection and eternal life.

Church services

The services of the church are conducted each day according to the church calendar. Parts of each service remain fixed, while others change depending on the observances prescribed for the specific day in the various cycles, ever providing a flow of constancy within variation. Services are conducted in the church and involve both the clergy and faithful. Services cannot properly be conducted by a single person, but must have at least one other person present (i.e. a priest cannot celebrate alone, but must have at least a chanter present and participating).

Usually, all of the services are conducted on a daily basis only in monasteries and cathedrals, while parish churches might only do the services on the weekend and major feast days. On certain Great Feasts (and, according to some traditions, every Sunday) a special All-Night Vigil (Agrypnia) will be celebrated from late at night on the eve of the feast until early the next morning. Because of its festal nature it is usually followed by a breakfast feast shared together by the congregation.

The journey is to the Kingdom. This is where we are going—not symbolically, but really.

— Fr. Alexander Schmemann, For the Life of the World

We knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth.

— Ambassadors of Kievan Rus (10th Century), Apocryphal quote from conversion of Kievan Rus.

Services, especially the Divine Liturgy, may only be celebrated once a day on a single altar (some churches have multiple altars in order to accommodate large congregations). Each priest may only celebrate the Divine Liturgy once a day.

From its Jewish roots, the liturgical day begins at sundown. The traditional daily cycle of services is as follows:

- Vespers – (Greek Hesperinos) Sundown, the beginning of the liturgical day.

- Compline (Greek Apodeipnon, lit. “After-supper”) – After the evening meal, and before sleeping.

- Midnight Office – Usually served only in monasteries.

- Matins (Greek Orthros) – First service of the morning. Prescribed to start before sunrise.

- Hours – First, Third, Sixth, and Ninth – Sung either at their appropriate times, or in aggregate at other customary times of convenience. If the latter, The First Hour is sung immediately following Orthros, the Third and Sixth before the Divine Liturgy, and the Ninth before Vespers.

- Divine Liturgy – The Eucharistic service. (Called Holy Mass in the Western Rite)

The Divine Liturgy is the celebration of the Eucharist. Although it is usually celebrated between the Sixth and Ninth Hours, it is not considered to be part of the daily cycle of services, as it occurs outside the normal time of the world. The Divine Liturgy is not celebrated on weekdays during Great Lent, and in some places during the lesser fasting seasons either; however, reserve communion is prepared on Sundays and is distributed during the week at the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts.

Other items brought to the altar during the Divine Liturgy include a gold or silver chalice with red wine, a small metallic urn of warm water, a metallic communion spoon, a little metallic spear, a sponge, a metal disk with cut pieces of bread upon it, and a star, which is a star-shaped piece of metal over which the priest places a cloth covering when transporting the holy gifts to and from the altar. Also found on the altar table is the antimins. The antimins is a silk cloth, signed by the appropriate diocesan bishop, upon which the sanctification of the holy gifts takes place during each Divine Liturgy. The antimins contain the relics of a saint. When a church is consecrated by a bishop, there is a formal service or prayers and sanctification in the name of the saint that the church is named after. The bishop will also often present a small relic of a saint to place in or on the altar as part of the consecration of a new church.

The book containing liturgically read portions of the four gospels is permanently “enthroned” on the altar table. Eastern Orthodox bishops, priests, deacons and readers sing/chant specific verses from this Gospel Book on each different day of the year.

This daily cycle services is conceived of as both the sanctification of time (chronos, the specific times during which they are celebrated), and entry into eternity (kairos). They consist to a large degree of litanies asking for God’s mercy on the living and the dead, readings from the Psalter with introductory prayers, troparia, and other prayers and hymns surrounding them. The Psalms are so arranged that when all the services are celebrated the entire Psalter is read through in their course once a week, and twice a week during Great Lent when the services are celebrated in an extended form.

Music and chanting

Orthodox services are sung nearly in their entirety. Services consist in part of a dialogue between the clergy and the people (often represented by the choir or the Psaltis Cantor). In each case the prayers are sung or chanted following a prescribed musical form. Almost nothing is read in a normal speaking voice, with the exception of the homily if one is given.

Because the human voice is seen as the most perfect instrument of praise, musical instruments (organs, etc.) are not generally used to accompany the choir.

The church has developed eight modes or tones (see Octoechos) within which a chant may be set, depending on the time of year, feast day, or other considerations of the Typikon. There are numerous versions and styles that are traditional and acceptable and these vary a great deal between cultures.[134] It is common, especially in the United States, for a choir to learn many different styles and to mix them, singing one response in Greek, then English, then Russian, etc.

In the Russian tradition there have been some famous composers of “unaccompanied” church music, such as Tchaikovsky (Liturgy of St John Chrysostom, op. 41, 1878, and All-Night Vigil, op. 52, 1882) and Rachmaninoff (Liturgy of St John Chrysostom, op. 31, 1910, and All-Night Vigil, op. 37, 1915); and many church tones can likewise be heard influencing their music.

Incense

As part of the legacy handed down from its Judaic roots, incense is used during all services in the Eastern Orthodox Church as an offering of worship to God as it was done in the Jewish First and Second Temples in Jerusalem (Exodus chapter 30). Incense is also prophesied in the book of Malachi 1:11 as a “pure offering” in the glorification of God by the Gentiles in “every place” where the name of God is regarded as “great”. Traditionally, the base of the incense used is the resin of Boswellia sacra, also known as frankincense, but the resin of fir trees has been used as well. It is usually mixed with various floral essential oils giving it a sweet smell.

Incense represents the sweetness of the prayers of the saints rising up to God (Psalm 141:2, Revelation 5:8, 8:4). The incense is burned in an ornate golden censer that hangs at the end of three chains representing the Trinity. Two chains represent the human and Godly nature of the Son, one chain for the Father and one chain for the Holy Spirit. The lower cup represents the earth and the upper cup the heaven. In the Greek, Slavic, and Syrian traditions there are 12 bells hung along these chains representing the 12 apostles. There are also 72 links representing 72 evangelists.

The charcoal represents the sinners. Fire signifies the Holy Spirit and frankincense the good deeds. The incense also represents the grace of the Trinity. The censer is used (swung back and forth) by the priest/deacon to venerate all four sides of the altar, the holy gifts, the clergy, the icons, the congregation, and the church structure itself. Incense is also used in the home where the individual will go around the house and “cross” all of the icons saying in Greek: Ἅγιος ὁ Θεός, Ἅγιος ἰσχυρός, Ἅγιος ἀθάνατος, ἐλέησον ἡμᾶς, or in English: Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal, have mercy on us.

Fasting

|

This section does not cite any sources. (November 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

The number of fast days varies from year to year, but in general the Eastern Orthodox Christian can expect to spend a little over half the year fasting at some level of strictness. There are spiritual, symbolic, and even practical reasons for fasting. In the Fall from Paradise mankind became possessed by a carnal nature; that is to say, became inclined towards the passions. Through fasting, Orthodox Christians attempt to return to the relationship of love and obedience to God enjoyed by Adam and Eve in Paradise in their own lives, by refraining from carnal practices, by bridling the tongue (James 3:5–6), confession of sins, prayer and almsgiving.

Fasting is seen as purification and the regaining of innocence. It is a practice of learning to temper the body’s primary desire for food. By learning to temper this basic desire of the body, the practitioner can more readily temper other worldly desires, and thus, become better enabled to draw closer to God in the hope of becoming more Christ-like. Through obedience to the church and its ascetic practices the Eastern Orthodox Christian seeks to rid himself or herself of the passions (The desires of our fallen carnal nature). All Orthodox Christians are provided with a prescribed set of guidelines. They do not view fasting as a hardship, but rather as a privilege and joy. The teaching of the Church provides both the time and the amount of fasting that is expected as a minimum for every member who chooses to participate. For greater ascesis, some may choose to go without food entirely for a short period of time. A complete three-day fast at the beginning and end of a fasting period is not unusual, and some fast for even longer periods, though this is usually practiced only in monasteries.

In general, fasting means abstaining from meat and meat products, dairy (eggs and cheese) and dairy products, fish, olive oil, and wine. Wine and oil—and, less frequently, fish—are allowed on certain feast days when they happen to fall on a day of fasting; but animal products and dairy are forbidden on fast days, with the exception of “Cheese Fare” week which precedes Great Lent, during which dairy products are allowed. Wine and oil are usually also allowed on Saturdays and Sundays during periods of fast. In some Orthodox traditions, caviar is permitted on Lazarus Saturday, the Saturday before Palm Sunday, although the day is otherwise a fast day. Married couples also abstain from sexual activity on fast days so that they may devote themselves fulsomely to prayer (1 Corinthians 7:5).

While it may seem that fasting in the manner set forth by the Church is a strict rule, there are circumstances where a person’s spiritual guide may allow an Economy because of some physical necessity (e.g. those who are pregnant or infirm, the very young and the elderly, or those who have no control over their diet, such as prisoners or soldiers).

The time and type of fast is generally uniform for all Orthodox Christians; the times of fasting are part of the ecclesiastical calendar, and the method of fasting is set by canon law and holy tradition. There are four major fasting periods during the year: Nativity Fast, Great Lent, Apostles’ Fast, and the Dormition Fast. In addition to these fasting seasons, Orthodox Christians fast on every Wednesday (in commemoration of Christ’s betrayal by Judas Iscariot), and Friday (in commemoration of Christ’s Crucifixion) throughout the year. Monastics often fast on Mondays.

Orthodox Christians who are preparing to receive the Eucharist do not eat or drink at all from vespers (sunset) until after taking Holy Communion. A similar total fast is expected to be kept on the Eve of Nativity, the Eve of Theophany (Epiphany), Great Friday and Holy Saturday for those who can do so. There are other individual days observed as fasts (though not as days of total fasting) no matter what day of the week they fall on, such as the Beheading of St. John the Baptist on 29 August and the Exaltation of the Holy Cross on 14 September.

Almsgiving

Almsgiving, more comprehensively described as “acts of mercy”, refers to any giving of oneself in charity to someone who has a need, such as material resources, work, assistance, counsel, support, or kindness. Along with prayer and fasting, it is considered a pillar of the personal spiritual practices of the Eastern Orthodox Christian tradition. Almsgiving is particularly important during periods of fasting, when the Eastern Orthodox believer is expected to share with those in need the monetary savings from his or her decreased consumption. As with fasting, mentioning to others one’s own virtuous deeds tends to reflect a sinful pride, and may also be considered extremely rude.

Traditions

Monasticism

The Eastern Orthodox Church places heavy emphasis and awards a high level of prestige to traditions of monasticism and asceticism with roots in Early Christianity in the Near East and Byzantine Anatolia. The most important centres of Christian Orthodox monasticism are Saint Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai Peninsula (Egypt) and Mount Athos in Northern Greece.

All Orthodox Christians are expected to participate in at least some ascetic works, in response to the commandment of Christ to “come, take up the cross, and follow me.” (Mark 10:21 and elsewhere) They are therefore all called to imitate, in one way or another, Christ himself who denied himself to the extent of literally taking up the cross on the way to his voluntary self-sacrifice. However, laypeople are not expected to live in extreme asceticism since this is close to impossible while undertaking the normal responsibilities of worldly life.

Those who wish to do this therefore separate themselves from the world and live as monastics: monks and nuns. As ascetics par excellence, using the allegorical weapons of prayer and fasting in spiritual warfare against their passions, monastics hold a very special and important place in the Church. This kind of life is often seen as incompatible with any kind of worldly activity including that which is normally regarded as virtuous. Social work, school teaching, and other such work is therefore usually left to laypeople. Ascetics of the Eastern Orthodox Church are recognised by their long hair, and in case of male monks, long beards.

There are three main types of monastics. Those who live in monasteries under a common rule are coenobitic. Each monastery may formulate its own rule, and although there are no religious orders in Orthodoxy some respected monastic centers such as Mount Athos are highly influential. Eremitic monks, or hermits, are those who live solitary lives. It is the yearning of many who enter the monastic life to eventually become solitary hermits. This most austere life is only granted to the most advanced monastics and only when their superiors feel they are ready for it.

Hermits are usually associated with a larger monastery but live in seclusion some distance from the main compound. Their local monastery will see to their physical needs, supplying them with simple foods while disturbing them as little as possible. In between are those in semi-eremitic communities, or sketes, where one or two monks share each of a group of nearby dwellings under their own rules and only gather together in the central chapel, or katholikon, for liturgical observances.

The spiritual insight gained from their ascetic struggles make monastics preferred for missionary activity. Bishops are almost always chosen from among monks, and those who are not generally receive the monastic tonsure before their consecrations.

Many (but not all) Orthodox seminaries are attached to monasteries, combining academic preparation for ordination with participation in the community’s life of prayer. Monks who have been ordained to the priesthood are called hieromonk (priest-monk); monks who have been ordained to the diaconate are called hierodeacon (deacon-monk). Not all monks live in monasteries, some hieromonks serve as priests in parish churches thus practicing “monasticism in the world”.

Cultural practices differ slightly, but in general Father is the correct form of address for monks who have been tonsured, while Novices are addressed as Brother. Similarly, Mother is the correct form of address for nuns who have been tonsured, while Novices are addressed as Sister. Nuns live identical ascetic lives to their male counterparts and are therefore also called monachoi (monastics) or the feminine plural form in Greek, monachai, and their common living space is called a monastery.

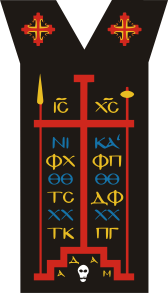

Icons and symbols

Everything in the Eastern Orthodox Church has a purpose and a meaning revealing God’s revelation to man. At the front, or eastern end of the church, is a raised dais with an icon-covered screen or wall (iconostasis or templon) separating the nave from the sanctuary. In the center of this wall is the entrance to the altar known as the “Royal Doors” through which only the clergy may pass.

There is a right and left side door on the front of the iconostasis, one depicting the archangel, Michael and the other Gabriel. The priest and altar boys enter and exit through these doors during appropriate parts of the Divine Liturgy. Immediately to the right of the main gate you will always find an icon of Jesus Christ, on the left, an icon of the Theotokos (Mother of God). Other icons depicted on the iconostasis are Saint John the Forerunner and the Saint after which the church is named.

In front of the iconostasis is the bishop’s chair, a place of honor where a visiting bishop or metropolitan will often sit when visiting the church. An Orthodox priest, when standing at the altar during the Divine Liturgy, faces toward the altar (typically facing east) and properly leads his congregation while together they perform the mystical sacrifice and pray to God.

The sanctuary contains the Holy Altar, representing the place where Orthodox Christians believe that Christ was born of the virgin Mary, crucified under Pontius Pilate, laid in the tomb, descended into hell, rose from the dead on the third day, ascended into heaven, and will return again at his second coming. A free-standing cross, bearing the body of Christ, may stand behind the altar. On the altar are a cloth covering, a large book containing the gospel readings performed during services, an ark containing presanctified divine gifts (bread and wine) distributed by the deacon or priest to those who cannot come to the church to receive them, and several white beeswax candles.

Icons

The term ‘icon’ comes from the Greek word eikon, which simply means image. The Eastern Orthodox believe that the first icons of Christ and the Virgin Mary were painted by Luke the Evangelist. Icons are filled with symbolism designed to convey information about the person or event depicted. For this reason, icons tend to be formulaic, following a prescribed methodology for how a particular person should be depicted, including hair style, body position, clothing, and background details.

Icon painting, in general, is not an opportunity for artistic expression, though each iconographer brings a vision to the piece. It is far more common for an icon to be copied from an older model, though with the recognition of a new saint in the church, a new icon must be created and approved. The personal and creative traditions of Catholic religious art were largely lacking in Orthodox icon painting before the 17th century, when Russian icons began to be strongly influenced by religious paintings and engravings from both Protestant and Catholic Europe. Greek icons also began to take on a strong western influence for a period and the difference between some Orthodox icons and western religious art began to vanish. More recently there has been a trend of returning to the more traditional and symbolic representations.

Aspects of the iconography borrow from the pre-Christian Roman and Hellenistic art. Henry Chadwick wrote, “In this instinct there was a measure of truth. The representations of Christ as the Almighty Lord on his judgment throne owed something to pictures of Zeus. Portraits of the Mother of God were not wholly independent of a pagan past of venerated mother-goddesses. In the popular mind the saints had come to fill a role that had been played by heroes and deities.”[135]